What I learned starting (and ending) a food business

A long post about margin and personal values

Last summer I started a granola business under this same brand – Probably Worth Sharing – and I shut it down six months later, despite having relatively good sales for a new business. Today I’m going to share why I started selling granola, what worked, what didn’t, and why I ultimately shut the business down.

The short version? Starting up any business, but especially a food business, is Level 9 Tetris.

It’s exciting and with enough tries you can make it work, but one wrong move and it's game over. Often we hear about the successes while the failures quietly fade into the sunset. But over 90% of small businesses fail, yet they don’t occupy 90% of the stories we hear, which makes learning from failure an individual experience.

So while I had a lot of good experiences with my granola business, today I’m going to focus on how difficult it was to offer an honest perspective to anyone who’s considering starting a small food business, and to ask yourself questions on how you could make it successful.

I will also be publishing the commercial granola recipes on my website at some point. A few are up after being requested by customers. Since the business came out of a YouTube recipe video I made for granola, most of the recipes were already published.

Why I started

I’m a great baker – but I am a home baker. When you’re a great home baker, almost everyone in your life will tell you something like:

“You should sell this granola!”

“You should open a bakery!”

“You should be on the Great Canadian Baking Show!”

Last year I tried all of these things. I quit my tech job in January 2023, my intent was to focus on my YouTube cooking show for a year, but through a series of large distractions I only made a handful of new recipe videos last year. Working alone, living alone, and without the distraction of colleagues, I found video creation to be very lonely and isolating work. I was my own roadblock and I missed having a team and community.

One of my distractions that I previously wrote about was my experience interviewing for The Great Canadian Baking Show – ultimately I made it through final interviews but did not get on the show. In interviewing, I learned that I’m not the kind of baker they want (or that would succeed on the show). My priority is on ingredient quality, flavour, and technique; the producers are focused on visual pizazz and storytelling, which makes sense for TV. There are bakers who can do both, but I am not one of them. Going through that experience helped me understand what kind of baker I am and want to be.

Based on that learning about myself, I decided to explore my age-old question: should I open a bakery? I had just published my granola recipe video on YouTube, and all of my friends said I should start selling granola. It felt like the perfect product to test out what a bakery could be like: it’s easy to make, shelf-stable, and I could sell it online.

I structured the granola business to get me into the local community. I would test it for six months to figure out if I liked it or not. In my mind this would be 1–2 days a week and I could still write this newsletter and make video on the side.

I vastly underestimated how much time and capacity this kind of business required.

What goes into starting a food business?

Food businesses are complicated due to the red tape involved – there’s a lot of food safety legislation (for good reason). This makes it very time consuming and expensive to start up.

The Province of Ontario, where I live, tried to change this in 2021, allowing home bakers to sell low risk food items, like bread, from their home kitchens. However, public health regulations are local. Laws in municipalities like Waterloo Region, where I live, supersede the Province.

In Waterloo Region, a home based kitchen needs to be:

In a home zoned for commercial baking use – which my house is not

In a separate kitchen from your living space, such as in a basement or garage

Compliant with full public health regulations for a kitchen space, with the exception of not requiring a separate hand wash sink (which is laughably cheap to put in in the context of all the other requirements).

Waterloo Region’s view of this law is that you must have a second commercial kitchen in your home. I don’t believe it follows the spirit of the law created for low risk food items (which includes bread and granola). While I appreciate the intent, after what I’ve seen working in a shared commercial kitchen, it’s not increasing food safety. It’s increasing the cost and burden for low risk bakeries to start up in a cost efficient, safe way. It’s causing new businesses to take on extremely high costs and rental contracts.

Many bakery items need to be baked and sold on the same day, so I decided to sell granola because it’s a shelf stable, packaged good that can be sold direct at markets, through retailers, and online. It would give me more flexibility to move product. If sales were bad I could hold off making new product until I sold inventory.

It’s 2–3 months of work to even get started

Given these requirements, I needed to find shared space I could rent. Here’s everything I needed to figure out before my first day in the kitchen:

Set up a business: I had already set up my sole proprietorship to handle my income from this newsletter, book sales, and YouTube, and kept the granola as another activity within this business.

Find a shared kitchen: I rented a shared kitchen space for 8 hours, one day per week in a shared kitchen. This cost $800/m. This was the minimum amount of time required to rent, and I was required to sign a 1-year lease that I could end after six months.

Get a business license to operate out of that kitchen: The business license itself is required to produce food products in the City of Kitchener. It costs $130/year. This required me to have the kitchen inspected, my product labels completed and approved by Public Health, and I needed my Safe Food Handlers certificate. This process took six weeks, but could take up to twelve weeks.

Get Safe Food Handlers: An online course that takes 8 hours and costs ~$40.

Find a place to sell granola: In my case that was online, at the Kitchener Market, and wholesale to retailers. This required a bunch of stuff:

An ecommerce platform, which was initially Squarespace, then Shopify.

A booth at the Farmer’s Market ($160/m), which required its own business license ($130/year), point of sale hardware (3% of sales), a physical booth, and signage, and marketing materials. I also needed to obtain approval from the Kitchener Market on the products I was allowed to sell.

A wholesale invoicing platform (Stripe, 3% of sales).

Get business insurance: I needed general liability insurance, as well as coverage for the shared kitchen, and for the Kitchener Market.

Set up business banking: This makes accounting much easier.

Packaging and labeling: I needed Public Health to sign off on my packaging since I was selling a retail product. To figure out packaging and labeling that was compliant with CFIA regulations, I used FoodLabelMaker ($50/m) to make CFIA compliant nutrition labels, and it also meant fixing my recipes in stone due to needing to match the printed labels. I then had to design and source labels, as well as bags for granola.

Make a website: I had to set up an online presence on my website, and ancillary services like Google Merchant Centre, Facebook and Instagram products, and figure out an online store.

Learn how to ship products: I had to open a Canada Post Business Account. Later, when I moved to Shopify I discovered the massive discounts Shopify has (compared to buying labels yourself) which cut my shipping costs from $22.50 to $10 per order.

Set up HST: For non-Ontario residents, HST is our combined Provincial and Federal sales tax (13%). You have to register for, collect, and remit HST once you sell more than $30,000 in one quarter. I had crossed the HST billing threshold quite quickly, which meant I had to register for HST and set up a call with the CRA to determine the HST status of granola. Granola is quite confusing in the HST rules. If it’s marketed as cereal? It has no HST. It’s zero rated, which means you can still get input tax credits (a rebate on the HST you spend vs what you owe). However, if it’s marketed as a snack food, like granola bars? Then it has HST. HST became further complicated since shipping costs for online orders have HST. This is what necessitated my move to Shopify, as Squarespace could not do zero-rated products + HST on shipping (a restriction in their platform for Canada only).

All of this work had to be done before I could make a single batch of granola for commercial sale.

The space creates challenges

I didn’t really know what questions to ask as I got started with making granola and very quickly ran into many restrictions based on the decisions I made for where I would make, store, and sell granola:

At the Kitchener Market: I had a small, 4-foot booth with no sink. Because I did not have a sink, I was not able to prepare samples at the Market. Everything had to be pre-packaged, including samples. Samples had to be pre-made in the commercial kitchen in closed containers. This meant I could only give out samples of dry granola, not with yogurt. If I wanted to sell parfaits, they all had to be pre-made (risking a lot of food waste if they weren’t sold). This also meant part of my kitchen day had to be dedicated to preparing samples, and it was another component to track inventory of.

In the shared kitchen: Because I was working in a shared kitchen, I could not make claims like gluten free (since I shared baking sheets with people making bread) or kosher (since the facility processed both fish and tallow). Not having these claims limited the appetite of health food stores to carry the product, which is where more affluent buyers who value organic products with compostable packaging shop.

Shipping limitations: In order to legally ship across Provinces, you need an interprovincial export license from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). This means you need to be in a CFIA-compliant kitchen, which I was not in. CFIA compliance is an increased level of food safety and inventory control management processes. This is so that you can do things like facilitate batch-level recalls in the case of food safety issues, like contamination. In order to legally ship to the USA, you need an export license, which requires CFIA compliance. It’s a whole process, it takes years.

Organic limitations: Ontario does not regulate organic claims, but as soon as you sell across Provinces you need a Canada Organic certification and be subject to an audit (which just means keeping a log of all your ingredient inputs). To sell to the USA you need to apply to transfer Canada Organic to USDA Organic. This means all product inputs going into the system must have Canada Organic and USDA Organic seals. It’s a whole process, it also takes years.

The shared kitchen had its own set of complications:

To find margin, I needed to buy ingredients at the pallet level. For example, 1kg of local organic oats cost me $2/kg, but only if I bought a pallet at a time. It was worthwhile, because as a consumer, those same oats cost $7.50/kg. I used an average of 50kg of oats per week. However, this meant needing more storage space – so I had to rent more storage space in the shared kitchen.

Pallet deliveries to the kitchen would show up whenever they wanted, with no notice – so on a random day, at a random time I would have to drop what I was doing to go deal with a pallet. Was a $4,000 order of ingredients safely delivered or left outside in the rain? Did someone receive it and is it now in the middle of their workspace, and my inventory is making someone else’s day worse? It was a surprise every time.

The shared kitchen was a very toxic work environment for many reasons: there was bullying and harassment from a specific tenant I shared space with. There was theft of my materials and tools. Every week the space and tools were left dirty by other tenants, which I had to re-sanitize before starting my shift. There were deficiencies that would have shut the kitchen down during an inspection, like the handwash sink being broken for a month. There was overloading tenants during exclusive use periods – once five different businesses were operating in the kitchen during the same shift (only two are allowed at a time). Often other tenants would be using my equipment during my shift. There was a lack of climate control, meaning ingredients like chocolate chips would melt together when stored at room temperature in the Summer. The water heater would fail in the Winter. When I brought up the issues, the landlord would respond with a shrug, and eventually turned to retaliation when I made complaints – making working there even worse. This is the worst environment I have ever worked in in my life, and I previously spent 8 years working in commercial kitchens.

Due to limited storage in the kitchen, I would have to bring finished product to my house for storage, and run order fulfillment from home. This always made me very uncomfortable because it’s not strictly compliant (everybody does it anyway). I did not want to create a pest problem in my own home by storing so much granola there. Eventually I bought a locked cabinet for the Kitchener Market to store product there, but that had its own challenges too in terms of physical access due to the Market’s hours.

This created so much extra physical labour because I did not have a stable place of business. I had to constantly shuttle 150–300 bags of granola (110 to 220lbs) from the kitchen to my house to the Market and back to my house every week.

Given how terrible my experience in the shared kitchen was, I started exploring alternative locations. I explored a few avenues, which included:

Find other shared space. Unfortunately, there is no other shared bakery kitchen space available in Waterloo Region with bakery sized ovens. There are shared kitchens for cooking, but they have small, home-sized ovens. The City of Kitchener is exploring building one at the Market, but with an even higher hourly rate, and ever changing opening dates due to a lack of funding. This went from September to February (and still no plan in place) while I was exploring this. Given the low margins in food businesses, small business owners are going to prioritize a bad working environment with lower costs, since compromising their own work environment is better than compromising on product.

I could build a kitchen in my basement, but it would require re-zoning my house to allow a commercial bakery in my basement ($10,000 for a zoning amendment with no guarantee of success) + renovating my basement to support a commercial kitchen ($50,000+) and commercial equipment ($75,000+). However I wouldn’t have a retail location, keeping many of my existing sales challenges, and I would need to convert my home insurance and mortgage to be commercial. It would be substantially complex and expensive work with no guarantee of success.

I could lease commercial space to build out my own kitchen space with a retail bakery. I was exploring this path quite seriously in October, just before my dad had a stroke. Working on this while my dad was in the hospital was very challenging. Another part of the challenge is granola: I would have to do a gluten free bakery to have the products be certified gluten free. Another challenge is location, granola is not a destination so there has to be foot traffic. I had found space I liked, but everything in commercial real estate operates differently than residential real estate. It’s slow. The occupancy date moved from November, to December, to February, and it’s February now and the building still isn’t ready for tenants. You are required to use commercial contractors, which dramatically increases costs for build-out. I had originally thought $200,000 would be enough financing to make this happen – but after getting closer to a final rental agreement and build-out costs, I would have needed at least $400,000 to complete a build-out, buy equipment, and have 1-year of operating capital to figure out the business. I would also need to personally guarantee payments on a 5-year lease, so if the business failed I would still be paying thousands of dollars in monthly rent out of my own pocket. I could have tried to squeak by with the financing I had available, but I’d be one crisis away from everything failing – and I was living through my dad’s health crisis at the time. So I walked away from it.

The margins are awful (unless you compromise)

I sold granola for $12.99 per bag, which is very expensive, but I needed this price point to have margin – the amount of money left after accounting for all of my costs to make one bag of granola. Note that margin is not profit, as you still need to calculate the cost of selling the product. This is just the cost to make and package the product.

The main cost I could lower was overhead: labour and kitchen costs; I didn't want to compromise on ingredient quality or compostable packaging. To lower overhead, I would need to optimize how I used my time on my kitchen day. On bake day, I needed to be able to do inventory, make as much granola as I could, make samples, move finished products out, and clean the space within an 8-hour shift.

In theory, working in the kitchen should have looked like this:

Spend 30 minutes on inventory, prep and pre-heating the oven

Spend 6 hours baking and cooling (overlapping packaging by 2 hours)

Spend 4 hours packaging (overlapping with baking by 2 hours)

Spend 30 minutes on cleanup

In theory, the oven was my limiting factor. I did some simple math to figure out if this could work:

Each baking sheet makes 5 x 330g bags of granola

I can fit 5 full baking sheets in the oven at once

Each bake takes 30 minutes

In 6 hours of baking, that’s 12 bakes

So 5 bags x 5 baking sheets x 12 bakes = 300 bags of granola per day as my upper limit

The bullet point version sounds like a great business. At $12.99 each that’s nearly $4,000 a week in sales! That’s over $200,000 a year in sales! Great for a 1-day a week business!

Reality check

But it turns out that packaging 300 bags of granola by hand takes 8 hours. I could have solved this by buying a $10,000 weigh-filling machine, but that’s a long-term investment. It’s the perennial small business question: do I spend $10,000 on equipment to save on labour? I can spend $200/week to have a human package granola. The machine only saves money after a year of use or scaling up the number of production days. Plus, there was nowhere to store it in the shared kitchen.

Because packaging took so long this meant in practice I could only produce 150 bags of granola per bake day if I was working alone, and only 200 if I had help.

It turned out that working in the kitchen was more like this:

Arrive to find someone else already using my oven, set to 500 degrees, and wait 2 hours for the oven to be free and cooled down.

Arrive to find equipment like bowls and utensils put away dirty, or my station left with other tenants materials, and spend those 2 hours documenting all of these issues and cleaning someone else’s mess so I can work from a sanitary environment.

Fall further behind in my schedule because the dish pit was left overloaded while another tenant went out for a smoke break, or there were five tenants working at the same time, which meant I could not continue working unless I did their dishes for them or put them on the floor.

Have my tools or ingredients mysteriously disappear, so I would need to run to the store so I could continue working.

This meant that in practice I needed help, and with help I could still only make 150–200 bags of granola per bake day. This made my costs look like this:

Kitchen: $180 per bake day

Helper: $200 per bake day ($25/h)

My labour: $200 per bake day ($25/h)

In practice I did not pay myself, but those labour costs need to be modeled anyway. Many people do not model their labour, but you need to model it into your costs even if you do not pay yourself. Assuming your business works you’ll need to backfill this role with someone you pay. If you don’t model this, you’re setting yourself up to lose money over the long-term and invest in a non-profitable business model.

These costs became my overhead. Using 150 bags per day, my overhead costs were $3.85 per bag of granola. For the full cost, I included:

Overhead: $3.85 per bag

Packaging: ~$1.50 per bag (this varied over time)

Ingredient costs: Average $2.75/bag (depending on flavour)

This makes my total cost (ignoring sales overhead) of ~$8 per bag. That’s $4.99 in margin! So great!

Actually, it’s not.

The Math Doesn’t Math

There is no girl math in a food business. You can only be delulu for so long.

It’s important to figure out everywhere labour goes into the business, which means needing to calculate how much it costs to sell and fulfill orders, and how much time goes into business admin work. Once you track your time you realize what your job actually is.

In my head I was starting a bakery, I would be a baker. When you start a small business you are in sales. Instagram promotion? You’re doing sales. Working at a pop-up market? You’re doing sales. Trying to get retail wholesale clients? You’re doing sales. Hustling samples at the Kitchener Market? You’re doing sales.

You have to pay salespeople. Sales is very hard work.

You have to experiment to find a market. All of the experiments have costs.

One experiment? I explored doing outdoor pop-up markets. This requires having a folding table, tablecloth, tent, signage, mobile point of sale, mobile inventory storage, and at the time I was selling parfaits so I also needed a cooler… and a Public Health permit. And to pay the costs of the market. Plus the costs of promotion, travel, setup, and teardown. I did not find the pop-up markets I did to be worthwhile.

Retail margin

Selling wholesale to retailers is a great way to change who you sell to: instead of everyone, it’s a smaller number of relationships with stores. But the math sucks.

Retailers want to have a 50% markup from the wholesale price. This means:

Wholesale price: For simple math, imagine I sell at a wholesale price of $10 to the retailer.

Markup: The retailer wants to markup that by 50% of the wholesale price: $10 * 50% = $5 markup

Retail price: That makes the retail cost $15 ($10 wholesale cost + $5 markup)

Price matching: The retailer wants to sell at the same price you sell directly, so that pricing is competitive across the market. This means your margin should be developed from your wholesale price, not your direct sale price.

Since I’m a small vendor and have good local relationships, I got away with slightly less than a 50% markup. I sold wholesale for $8.99 and retailed for $12.99. This is ~45% markup.

If you remember, my cost per bag of granola is $8. This means I only took home $0.99 for every bag of granola sold at retail. I sold quite a lot through retail, but I did not make a lot of money.

At Vincenzo’s, on demo day weekend, we sold over 200 bags of granola in two days. It felt like a resounding success. So much momentum! The people love granola! It’s an investment in recurring customers!

However, at wholesale prices that’s only $200 in margin. For demo days, I had to staff Vincenzo’s with two people for two 8-hour days. That makes the sales labour cost $800, not to mention all the time that was involved to win Vincenzo’s as a customer and the pre-work to set up for demo days.

Despite the “success”, I lost $600 on the Vincenzo’s demo days (they were still worth doing and a lot of fun given my personal circumstances). Theoretically, this is an investment into a market and long-term retail relationship. The goal is to get new customers hooked to become repeat customers, and measure this based on the customer lifetime value, not just the single purchase.

I had great repeat customers at Vincenzo’s, they’re an exceptional retailer and great to team partner with. This type of work is worthwhile, but I’m sharing this negative view as a sobering reminder of the hard costs of this type of business. You cannot blindly mistake momentum for profitability.

Retail client management is hard work

There’s a perception that getting into retail locations means you’ve made it, and you’ll fly off the shelves. In practice, retail sales management is a lot of work:

You’re investing the time in going door-to-door to meet with shops with your sales pitch, or partnering with a co-packer (who has their own cut of margin) who already has the relationships.

You’re gambling on first order payments. Will the product sell? Will they pay? Retailers really have most of the bargaining power here. Vincenzo’s wanted our first order on consignment, meaning I would only be paid after the inventory was sold (or returned after 2 months). Other retailers took 90–120 days to pay, and only paid after repeated reminders. If you’re selling to small businesses you don’t have relationships with, start from a cash on delivery (COD) model if you can.

Orders still have to be invoiced, packed, and delivered, which is all labour that must be accounted for.

For mid-size independent retailers, you need to check inventory and remind them to re-order.

Since I had such a slim retail margin, that quickly disappeared when you considered the costs of managing the relationship and fulfilling orders.

My friend Nigel, who loves sales (I do not), really helped me here. He also researched what it meant to get into larger independent retailers with five or more stores, and with chain retail. As a small vendor you have very low leverage. In many cases, a grocery store contract would look like this:

Exclusive purchase rights for specific markets, which would sabotage your relationships with independent retailers

Products would be purchased on consignment, so you’re only paid after sales are completed after a specific time window

They have long return windows, so if product doesn’t sell it’s returned to you (often after it’s staled or expired so you can’t sell it anywhere)

They want a guarantee on markup, which means the retailer can lower your price if they can’t move product at your suggested price. The retailer could discount granola to $5 instead of returning it. They would want a guaranteed 50% markup. At $5 retail, the whole wholesale must be $3.25. That means I would owe them the difference between what they paid ($8.99) and what they could sell for ($3.25). It's a high reward if it works, and a great way to lose money if you don’t test the market enough before pursuing larger retailers.

I also tried listing on Faire, but without offering substantial discounts and samples, it’s very difficult to get retailers to take a bet on a new product. My original packaging was also not appealing for the Shoppy Shop type buyer. The pricing model on Faire requires you to guarantee the same price you sell anywhere else, but Faire takes 10%, so ultimately that ate any margin I had in the product. Investing in selling on Faire just didn’t make sense for me.

There was a lot more to explore in retail – like offering packaged free samples – but packaging is so expensive from both a physical cost and labour point of view – that I did not want to invest anymore time or money here.

Farmer’s Market Margin

The Kitchener Market was, conceptually, the place with my highest sales margin. A direct sale to the customer! And for a few months it was great: I would sell out 100–150 bags of granola every Saturday. But the Kitchener Market is very seasonal. By the time winter rolled around I would sell ten bags of granola on Saturday.

Is granola just seasonal? Is it the product? Is Kitchener excited about supporting “new” but not recurring? Is it the “we’re not technically in a recession but everyone’s tightened their wallets” economy? Or is granola a grocery store purchase? I didn’t have the same seasonality impact at retailers.

The last few months at the Market didn’t work for me because of the high operating costs:

I would need two hours of labour in the kitchen every week to make samples for the Market, since they had to be pre-made and sealed. That’s $50 of labour and $50 in materials for sample cups and product each week.

The Market needs inventory management, setup and teardown each week. So while it’s open 7am–2pm, it needs to have someone there at least 6:30am–2:30pm. That puts weekly labour cost at $225 per week. If I wanted a Saturday off I would have to find someone to work for me and train them.

The booth cost was $40 per week.

That makes the operating costs $365 per week.

For direct sales my margin was $4.99 ($12.99 less $8 in costs). That meant I needed to sell at least 73 bags of granola per week to cover my operating costs of $365 (4.99 margin * 73 bags = $364 in margin). Anything over that was profit, anything less and that week operated at a loss. For the last 3 months I was losing money every single week operating out of the Kitchener Market.

I tried adding additional products to increase weekly return to the booth, like selling vegan yogurt – but that vendor I sourced from had quality control issues, and I had to throw out/refund yogurt that had gone bad quite often. I tried selling parfaits and caramels, which sold very well, but there was so much complexity in fitting this into my limited kitchen schedule and limited storage that I simply couldn’t do it all. Because I had no sink, I could not prepare these on demand at the booth. I was creating so many distractions from the core business (granola) when the problem is that the sales channel was not effective.

Don’t get me wrong here: I want the Kitchener Market to work. I love the Market. I have lived beside the Kitchener Market for 10 years. I shop there all the time. It’s a core part of Kitchener’s identity and downtown. But the team running the Market, who are great, are not set up to enable the Market to be successful. There is zero marketing for the Kitchener Market. Marketing is run by the City, not the Kitchener Market team – which is a huge disgrace. It means experiments, like the Wednesday Market (which I took part in – sales and foot traffic both sucked), are huge failures because nobody knows they exist. Nobody knows that the Kitchener Market is great in the Winter (or maybe they don’t want to walk in the cold).

The Kitchener Market worked hard to bring in so many cool new vendors and nobody knows they are there and the team running the Market has no way to tell anyone about them.

Online Margin

Online is a very difficult business due to the costs of shipping. People do not want to pay for the cost of shipping. Buying my own shipping labels from Canada Post cost an average of $21.50. The costs are the same whether I ship one bag or six bags of granola. And then there’s the cost of boxes! Boxes cost $1–2 each. And then there’s the costs of tape, and paper padding, and printing shipping labels, and the labour costs of packing boxes and getting them to the post office! And replacing shipments when there’s damage, like a bag of granola pops open.

To offer free shipping I calculated that when I sold six bags of granola at a discounted price of $75, I had enough margin ($4.99 * 6 bags, minus $2.94 discount = $27) to cover the cost of shipping and still make $5.50 to cover the labour costs of packing and shipping orders. It sounds great in theory, but who wants to buy 6 bags of granola at once, particularly bougie expensive granola that they’ve never tasted?

And who wants to pay $20 to ship a single bag of granola, making the cost $35 for one bag of granola?

Once I moved from Squarespace to Shopify for my online store, I could use Shopify’s shipping tools to calculate shipping costs per order and pass that right to the consumer. Shipping costs went down to $10 per order, but it’s still fairly prohibitive when you can head to the nearest grocery store to buy Harvest Crunch for $4.99, or walk to Legacy Greens to grab my granola without the shipping costs. Better for the customer, worse for my margin.

I started to question if I should run online at a loss: lose money on shipping to generate online orders, to create repeat customers and momentum. Or do I run this profitably and scale at a slower pace? I chose profitability. I thought about offering free or $1 samples, but the logistics of safely packaging and shipping those economically was something I didn’t have capacity to figure out.

The biggest turning point online was when I did a discount on my old packaging – dozens of people were ordering 10 bags at a time. I can’t believe how much a modest discount encourages orders. Discount week was huge for me (at the expense of margin).

Other notes on online

I don’t have a car, so my options for shipping online orders was to either walk them to Canada Post (a 1km walk) or have Canada Post pick up from my house in 1–2 days (delaying orders getting out). In order to have Canada Post pick up from my house, I would have to use my home address as the “From:” address which I wasn’t comfortable with.

I tried integrating with a wide array of online tools – Facebook and Instagram Marketplace, Google Merchant Centre, and experimented with running Google Ads. My background is online marketing, but I could not get the online store to convert, I suspect because of shipping costs. I spent over $1,000 on experiments that really didn’t generate any sales.

If you are exploring an online store, Shopify has a much more robust integration into these social selling systems than Squarespace. Speaking of Squarespace, I started there because it’s what I know and my existing website was already on. Eventually I moved to Shopify because of the HST compliance issues I listed above. I used Square for my Kitchener Market presence. Eventually I moved both of those, and wholesale ordering, to Shopify. If I did it again I would use Shopify for everything from day one. The integrations and compliance for Canadian sales are substantially better, and the savings on shipping costs will help drive sales.

Lastly, turning your home into an online fulfillment center is a terrible experience. This was another downfall of working out shared kitchen space. I lost the use of my dining room as it became filled with cardboard boxes, tape, printers, packing paper, and granola. It was unrelenting chaos.

Time suck

In my mind this was going to be a casual, fun baking experiment – a small business I can run on the weekends. I’d get to be in the community, get some social time, play around in the kitchen, and still have time to have a life and make YouTube videos.

I was very wrong.

Here’s what a typical week looked like for me:

Monday: Apply for grants and other funding, work on grant-related work, research business strategies, work on business strategy, accounting, and admin.

Tuesday: Online order fulfillment, photography for social posts, social media scheduling, replying to so many online messages, wholesale account follow-ups, wholesale account sales, and invoicing.

Wednesday: Bake day planning, grocery shopping, ingredient inventory management and ordering.

Thursday: Wake up at 5am so I could eat and shower before work. Pack the car at 6:30, get to the kitchen for 7:00. Work until 3:00 without a lunch break (no time!). Pack the car, unload granola at home. Eat at 4:00pm.

Friday: Fulfill wholesale orders, inventory for the Market, pack for the Market.

Saturday: Wake up at 5am so I could eat and shower before work. Leave for the Market by 6:15, work until 2:00pm without a lunch break (who’s going to watch the booth? I can’t take my Invisalign out at the booth to eat there.). Pack everything up and carry it home. Eat empanadas for lunch at 3:00.

Sunday: Rest?

How’s that for my sweet one-day a week job? Now imagine this chaos of adding in demo days, pop-up outdoor markets, my dad being in the hospital for two months, and trying to have a relationship.

A business like this is a relentless pace of trying to generate awareness and create sales and not conducive to having anything else in your life. It was never ending and exhausting.

On social media everyone saw the success, and behind the scenes I was falling apart – having lost my ability to stop, to rest, to have fun, to be present. I was a mess.

Packaging

I’m a stubbornly values driven individual. So when it came to packaging I chose to go with compostable. Compostable packaging is relatively new. It’s 3x the cost of disposable packaging. Initially, to keep my upfront costs down, I went with blank compostable bags that I put compostable stickers on. This was high in labour costs, but low in upfront commitment. These compostable bags cost $1.94 each once you factored in the labour of stickering them, but I could buy as few as 200 at a time.

Eventually I got printed compostable packaging from RooTree, based in Burlington, Ontario. RooTree has a small business program called The Pouch Collective, where they pool small orders together to give you at scale discounts. Everyone who’s doing the same size bag runs on the same day to save costs. For comparison, a small run of printed compostable bags would normally cost $2.05 per bag, but with the Pouch Collective discounts they were only $1.37 per bag. You can get a quantity as low as 500 units.

You have to follow their timing to get this discount. I started this process in August, and due to miscommunications within their team, I missed the deadline for the September program (by one day). This meant I did not get my order until just before Christmas. When I placed the order I was excited about the granola business, and by the time I got the order 3 months later I decided to shut down the business. The quality of the bags and printing is great, and I’m very pleased with them. They look very professional. They feel nice. They stand up and stand out in retail. And I spent $7,500 on bags I am not going to use.

Deciding that I would give up an investment of thousands of dollars on unused packaging was a difficult decision, but was the right one for me to make.

Similarly, I don’t expect many other small business owners to make the choice to go compostable at current prices. Printed conventional bags – meaning, throw them in the trash or make ocean waste – would cost $0.60 each. That’s a difference of $0.77 in margin per bag, which would nearly double my wholesale margin. But I did not want to compromise my values or add more plastic waste to this planet to create profit for myself. I would rather do something where I can add value to the world, not create further harm.

The costs of compostables will come down over time, but these are new processes and new materials. We need government programs to subsidize these costs until they can become competitive with conventional materials made from fossil fuel byproducts.

Deciding to wind down

Deciding to wind down the granola business was very difficult, but I think based on the math in this post, very obvious. It was happening at a very difficult time of my life. My dad was just out of two months in the hospital, my boyfriend at the time had just broken up with me, sales at the Market were miserable, and I had just made these large investments into the business – like spending $7,500 on packaging.

Was I making this decision for the right reasons? Or was I trying to control something when everything else was horrible?

But I know myself well. I’ve thought through the whole business and the math didn’t math.

Sure, I could have pushed through all these challenges. I’ve done it before. I did that with my software startup, FunnelCake. But I also know that I burned myself out doing that. FunnelCake was a very difficult business (a story for another day) and now granola was proving to be a very difficult business. I feel that I’ve had enough difficult businesses for one lifetime. It’s not something I need to prove to myself. I’d rather be content and spend time with the people I love.

The decision was made complicated because I had everyone else’s opinion, asked for or not, on the decision.

“You were so happy in the summer when you started the granola business, I’ve never seen you so joyful!”

While true, I started the granola business the same day I started dating someone. The fun around Granola Daddy is only because of my ex, who made up the name for me on our first date – he was also my first customer. Having lost both the granola business and the relationship, I can say with certainty that it was the relationship that brought that joy everyone felt.

“The product is so good!”

Great, then why aren’t people buying it? Why aren’t you buying it?

“You just made such a big investment, you’re just going to walk away from that?”

Yes, why would I choose to be miserable for years because I made a bad financial decision, when I can move on instead? I often joke with friends that “I’ve spent more money on stupider things” when I buy something frivolous. While I can’t say that here, I’ve at least set a high bar for that statement in the future. I recognize that I’m in a very privileged position to be able to walk away from this business without negatively impacting anything except my ego and my bank account, and many people feel trapped by the time they get this far into a business financially.

The good that came of it

This is a mostly negative post, but there was a lot of joy that came out of this experience for me.

Hosting the Bake-A-Thon for Food4Kids Waterloo Region was one of best things I’ve ever done in my life. It was fun, it was fully inline with my value system, and it was a huge success. It also helped me see where my skills are in grassroots community marketing, leadership, and management.

Even while shutting down I was able to do some good: in January I donated over 500lbs of ingredients I had left – like oats, nuts, seeds, and oils – to Tiny Home Takeout in Kitchener, so the ingredients could be put to good use feeding those in need in our community.

I got to have a lot of fun with my friends: Kelly did her best Costco Sample lady impression at my booth at the Market. Nigel helped with wholesale and worked at the Market with his son. Nick helped weigh and vacuum seal ingredients. Jin Sol stickered bags. The Humble Lotus made sushi with granola (ask for the cookies and cream cheese eel). Chantalle, my Market booth neighbour, became my Saturday company. Elaine said “… but what if we got Elsa?” and then did. Jordan from Legacy Greens said she would sell my granola when it was just a YouTube video, and then actually did sell it when it was a retail product – as well as sharing her incredibly helpful business advice.

Then there’s everyone who went to every grocery store in Waterloo Region to find me organic citrus each week. And my dad, who loved to come hang out in the kitchen every week, he always swept the floors and helped me cart the granola to-and-from the kitchen to my house.

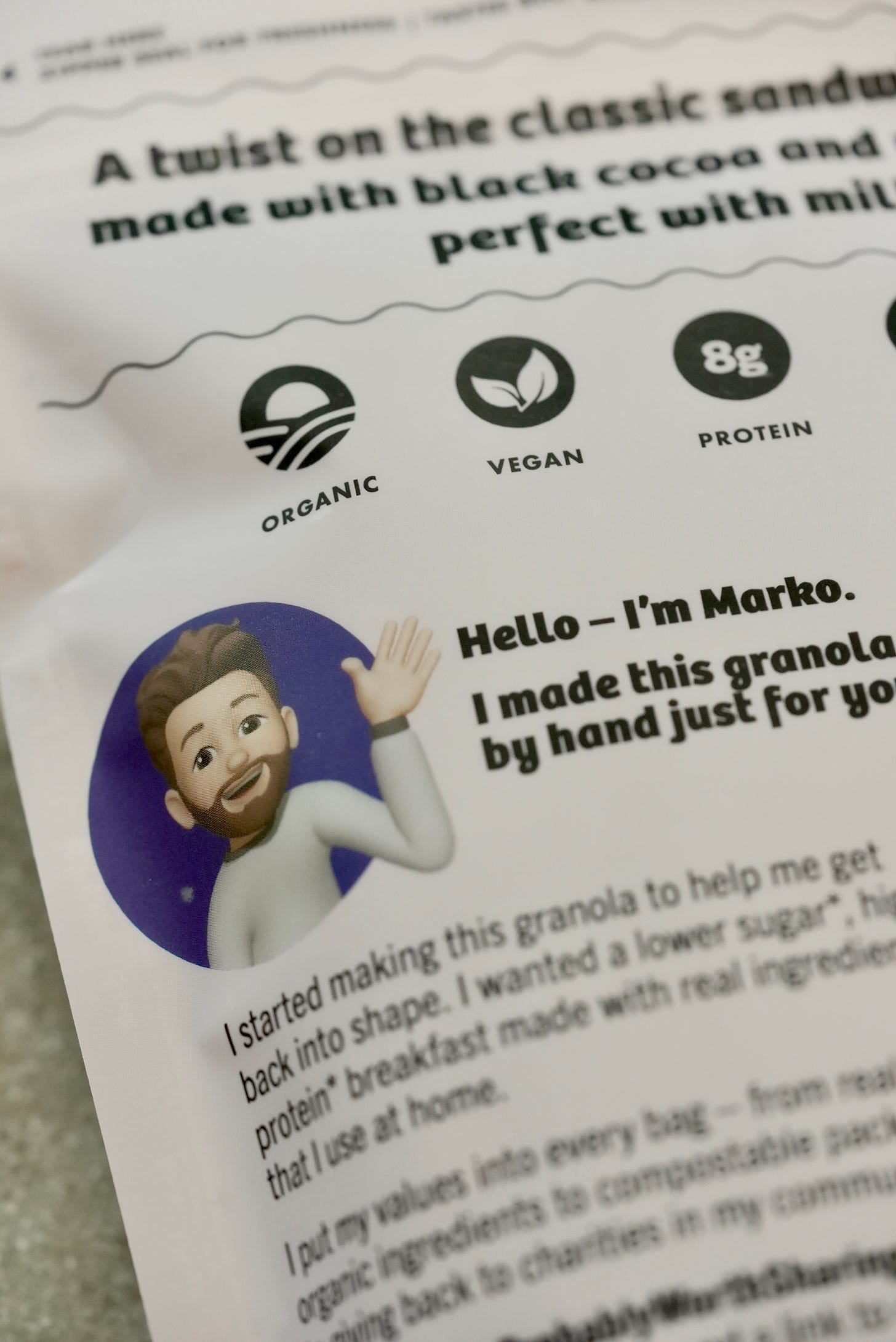

So much of the fun I had came from my relationship at the time. My ex named me Granola Daddy when buying the first bag of granola I ever sold. He helped me run the Bake-A-Thon, he came up with ads I ran at local movie theatres, wrote the copy for the new packaging, suggested the colour blocked photo shoot, Memoji Marko, and so many other ways he supported me during this time.

I’ll be forever grateful for the joy that all these people brought into this otherwise bad experience. It’s the people who make the work worth doing.

I’m also glad to see I stayed within my value system, and I moved on when my values would need to be compromised. For example:

I stayed with more expensive compostable bags instead of switching to disposable packaging, even though it was 3x more expensive.

I stayed with locally sourced ingredients and suppliers, even though it was 50% more expensive.

I stayed with organic ingredients, which are often 50% more expensive.

I kept the quality of the product instead of reducing the quantity of expensive ingredients (like nuts and seeds) and replacing with cheaper fillers, even though that would have improved margin.

I paid anyone who helped me a living wage, instead of minimum wage, at the expense of margin.

I kept my work/life balance and tried my best to maintain my relationships.

It’s easy to chip at these values one by one, and years later no longer recognize yourself or what you’re doing. I made a promise to myself when I started that I would not compromise what I believe in for the sake of business growth. I always said that if I can’t do it within my values system, I will not do it. I’m proud that I stuck by that promise to myself.

I also learned that I don’t want to do this kind of production work full time, which is better to learn before investing in my own kitchen. I think in the context of a bakery-cafe things would be different – there’s more room for fun, for relationships, for experimentation, for a team – but when it comes to a direct-to-consumer retail product, and working out of transient locations, this is not a business I enjoy. I do not want to bake the same thing at scale every single day. I do not want to be subjected to toxic work environments I can’t change.

For me, baking is a place for experimentation and finding joy. It’s a creative pursuit, not a labour. Turning it into work ruined it for me. In losing my love and energy for baking I lost the way that I made space for myself at home. That’s not going to be true for everyone, but it’s true for me.

I can’t say that the negative experiences, particularly how toxic the kitchen environment was, didn’t have an impact on how I view this experience. But the cost of having my own commercial kitchen is too high, especially given the challenges the business faced.

It’s also a question of what kind of life I want to have. What does work enable me to do? To have the same take-home pay as I made in my last role in the tech industry, I would need to sell over 1,000 bags of granola in direct sales, or 5,000 bags wholesale, every single week – a hilarious task given I could make 150–200 bags per week. To produce that much is an entirely different scale of production and investment into the business that would take years to achieve – if at all. It would also require a whole team to execute, which then multiplies those numbers even further.

Over the past few years I’ve made some amazing friendships in the food and small business community, meeting new friends with their own pop-ups and restaurants and stores. Some of these pop-ups and restaurants and stores have shut down. Before I did this myself I wondered why – I loved their products, I loved the reason to see them in the community, I didn’t understand why they stopped. Now I do, and I wanted to share this so you understand why I stopped, too.

There are so many other lessons to share here – around commercial recipe development, packaging design and compliance, social media, wholesale, community development, and I could probably write a whole book about the drama that happened in the kitchen – but I am closing this chapter. I want to move on from it onto topics that bring me joy in the kitchen. Someone else can share those lessons.

In the end I decided to stop the business, accept the loss on my investment into it, and move on with my life – and get a more traditional job again, somewhere I can do some good in the world.

What’s next?

As far as this newsletter and my YouTube channel are concerned, I am going to continue these as creative pursuits, but not primary income sources. Over the last year I learned that once I monetized my newsletter and video content I lost the joy I felt in the work. I struggled with the tension of asking for paid subscribers, of feeling forced onto a never ending commitment of content, and asking if I’m “creating value” or “creating for the algorithm” instead of, well, creating because its fun to create. I often felt so much guilt and shame if I didn’t keep up the pace of content I set out for myself.

Of all the work I’ve done over the last year, this newsletter has had the most impact on the outside world. The content people loved most are the pieces that only loosely fit the value proposition I made for the paid subscription. The content people love is about vulnerability. The piece about my mom dying, about The Last of Us, about my weight gain and weight loss, and about the impact my dad’s stroke had on my life. Sure, people loved the bean recipes, but you can get bean recipes from anyone. I felt, and continue to feel, uncomfortable charging people for “well, maybe I’ll write something meaningful and you get no additional value, you’re just giving me money because you want to!”

A few weeks ago, I silently paused my Substack paid subscriptions, so any paid subscribers should not have been charged for a renewal (if you did please feel free to ask for a refund). I’ll continue writing this newsletter, but without the pressure of weekly growth to drive a sustainable living – instead focusing on the stories I want to share, as time and interest allow me to write. I’ll also be moving off of Substack once I have time to figure that out, because demonetizing Nazis should be an easy decision that Substack’s leadership team just won’t make.

It’s funny to reflect on YouTube in all of this. When I quit my tech job in January 2023, video was meant to be my main work – but I only produced a few recipe videos and a few experiments last year. I went on sidebar (this newsletter!) after sidebar (ebooks, real books!) after sidebar (baking show auditions!) after sidebar (granola!) after sidebar (my dad), all without really doing the work I intended to. I learned a lot about what motivates me through that process.

Despite that, in October one of my videos – whole roasted cauliflower – took off. It has over 350,000 views and so far I’ve earned over $2,000 from just that one video. But I put 80 hours of work into that video, which means I earned $25/h from making it. And that’s the only video I made real money from. Sure, if they all took off like that I could make a real living. But I don’t know that that’s the life I want, because it’s very lonely to make videos alone at home, and the revenue is not there to hire a team. (For those who don’t know, I film and edit my videos entirely by myself using 3 camera on tripods, and lights mounted in my ceiling. You can learn more here.)

My hope is that back to a regular work schedule, video will return as a creative outlet for me. But for now it still feels too intense to commit to.

So this ends my year of experimentation in food as work, and begins my year of rebuilding with food as a creative outlet for joy.

Onwards,

Marko

Marko, thank you for writing such a detailed account of your experience with your start-up and your year to explore a new path in your life. I'm curious to see what you create out of all you've learned. I love your clear, thoughtful process of deliberate, conscious decision making rather than panicked, knee-jerk reactions to 'make a profit.' Do you think the infra-structure around small businesses is broken? Do you see what sort of changes or modifications would help create a better environment? I wonder if your experience and insights might lead you to some sort of political role in your local community.

Will you continue to write posts here while you figure out what to do next? I very much enjoyed your posts about food and think your videos are excellent. I wonder if you gave yourself enough time to establish a base. A year isn't a long time given all of the things you did.

I wish you all the best in your life, and hope that you continue to share on some level going forward.

Wow. All I can say is Wow! What an eye opener about all that is involved in something as seemingly simple as selling granola! All of my life people said I should do catering or sell this product or that. You would make a killing, they said. But for me, I seemed to inherently know that once I was cooking as a business, it would take all the joy out of it for me. I am also a values -driven person and I would go the extra mile to make things great at the expense of my life and my health and my bank account! But…. The thing that stood out to me the most from your amazing letter, was the fact that any commercially sold food product out there and being successful has most likely been compromised in some way. So not only is it more expensive than making your own granola ( or whatever) at home, but the ingredients are lesser than you would use at home. Tragic isn’t it? I hope you find new joy and peace in your new path.