April is Earth Month, and this month I’m going to focus on sustainability efforts in the kitchen. This week is focused on how to have a plastic-free kitchen.

Probably Worth Sharing is a reader supported publication. Please consider a paid subscription to support my work.

Composting! It turns trash into soil.

Composting is one of the best options humans have to create a circular ecosystem, where the items we need for daily life are returned to the earth in a way that creates life and restores ecosystems.

We currently live in a linear system, where resources are used to produce goods, which are turned into trash, which then stay in long-term storage (landfills) for whatever creatures inherit the earth after humanity is gone.

Composting is great. Composting is the future. But compostable isn’t always compostable.

What is composting?

Composting returns products back to the earth and creating rich soil to grow new plants by using worms, bacteria, and fungus to break down materials into fertilizer. Composting diverts waste from landfills, as much as 28% of waste heading for landfills can be composted instead. Instead of being a permanent part of our landscape, it returns to and enriches the earth.

Composting helps move us from a permanent impact into a sustainable, circular impact – a cycle – where human impact is balanced between consumption and creation.

Composting is very complicated to talk about, because how it's done and what can be composted varies tremendously based on technology and material science, all of which is very locally dependent.

Composting has a few key categories:

Biodegradable – in a natural environment, such as trash left in a forest, the material will break down over time (ideally without creating toxic byproducts that end up in the ecosystems). Materials like unbleached paper and egg shells are biodegradable.

Marine degradable – if trash makes its way into the ocean, the ocean – through force, water, and bacteria – can break it down (ideally without creating toxic byproducts that end up in the ecosystems and in the food chain). Many compostable materials, like bioplastic / polylactic acid (PLA) are not marine degradable – so they can still leave a permanent impact if these materials don’t end up in a suitable composting system.

Home compostable – Home composting systems tend to work over long periods of times and are suitable for most organics, with the exception of meat, bones, dairy, and bioplastics like PLA.

Home and industrial vermicomposting – vermicomposting uses worms instead of aerobic bacteria to decompose materials. The rules are similar to home composting.

Industrial static composting – aerobic bacteria and fungi are seeded into a large compost pile, outdoors, along with shredded paper. As the paper decomposes it creates air pockets, since the bacteria and fungi need oxygen to thrive. This is a low effort, but land intensive method of composting which can handle most materials, including bioplastics.

Industrial windrow composting – similar to static composting outdoors, but machines plow the materials in piles called windrows, which are tilled to aerate them, speeding up the process. This is another land-intensive and labour intensive process, but it works really well for handling a wide variety of materials and can work in 120-day cycles. Many suburban areas use windrow composting as they have the space for it.

In vessel composting (IVC) / bioreactors – bioreactors are closed, industrial composting systems that operate at higher temperatures, which sustain the bacteria and fungus (think of it like yeast or sourdough starter) at their optimal temperature, speeding up the entire process. The methane produced by composting can be easily captured and turned into fuel. Many larger cities use this method because it requires the least amount of land and can work on 60–90 day cycles, but it also limits the types of materials that can be composted – no bioplastics allowed.

What does compostable mean?

Compostable is a loose term – it means biodegradable under the right set of circumstances. But not all materials can break down in all composting systems. For example, bioplastics like PLA will not degrade in nature, or the ocean, or in bioreactor composting systems.

You need to consult your local waste management guidelines to determine what can be composted in your system.

For backyard composting, you can compost almost any organic matter in any system – unbleached paper products, produce, egg shells, plant matter, and hair.

In municipal/industrial composting systems, you can also compost all of the above plus meat, bones, dairy, food-soiled cardboard (like greasy pizza boxes, which can’t be recycled).

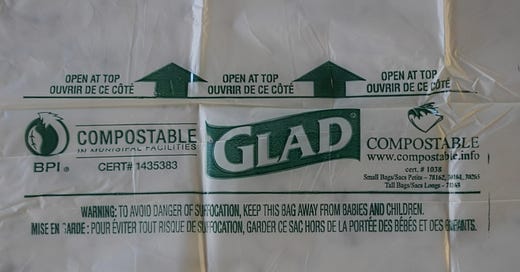

In only some systems can you compost bioplastics, frequently called “compostable bags” and “compostable packaging” – for example, you can compost bioplastics in Waterloo Region (where I live), but not in Toronto, New York, or Los Angeles. This means that some systems can’t support things compost bags, PLA-lined paper (like coffee cups and take-out boxes), clear bioplastic clamshell packaging, coffee pods (lined with PLA), and pet waste. Aspirational composting these might make you feel good but increases the cost, maintenance, and waste in the whole system. For example, Toronto has a shredding-and-filtering sortation system before the bioreactor that removes all plastics and bioplastics and diverts them to landfill.

Never include recyclables like glass, metal, or petroleum-based plastic in your compost. Remove all elastic bands (rubber/plastic), twist ties (metal), and stickers (plastic). Do not include solid wood, such as chopsticks and toothpicks.

How do I know what’s greenwashing?

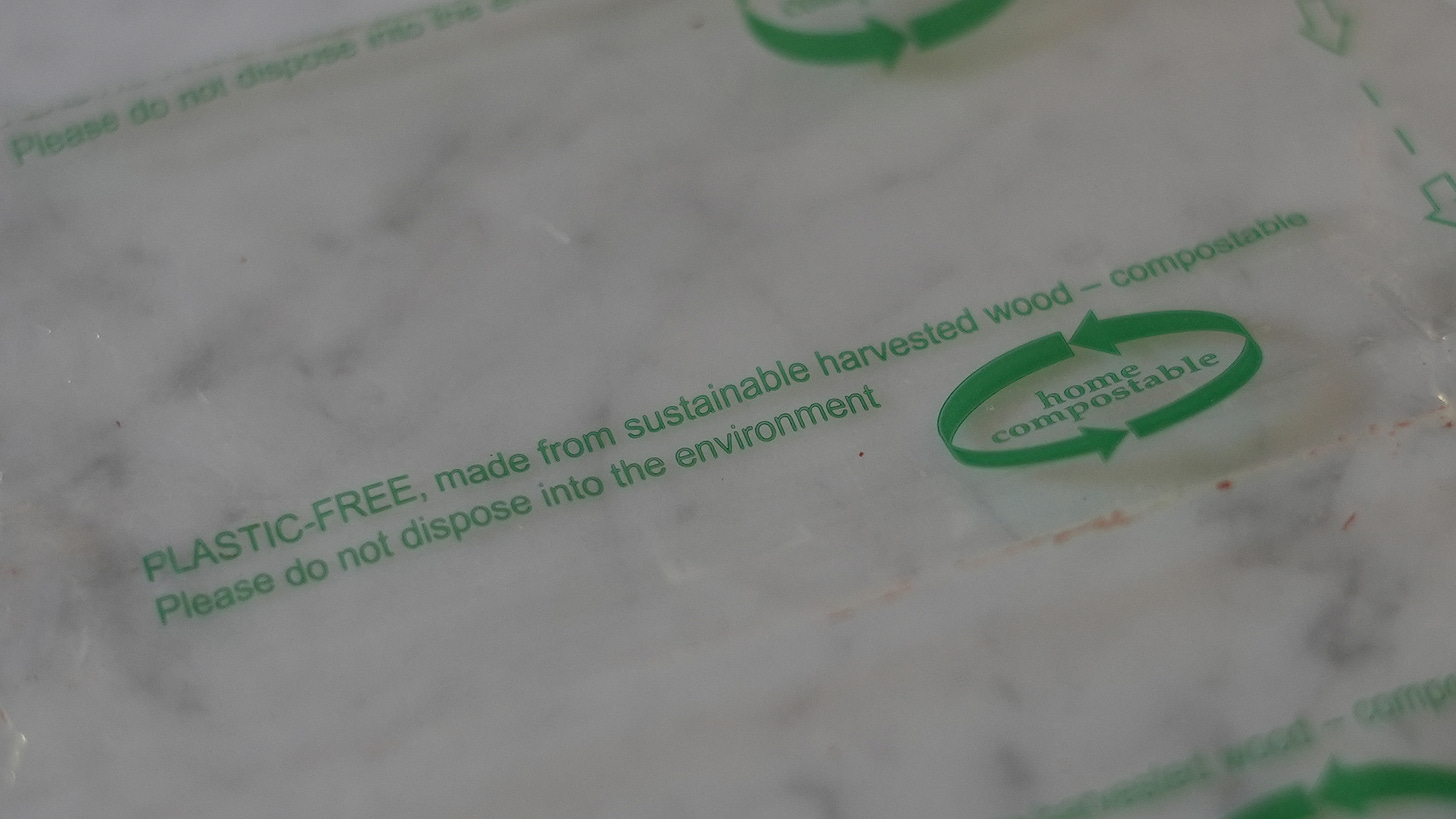

There are two kinds of misleading products here – products that are certified compostable, but within a municipal system that doesn’t support those products; and greenwashed products that appear compostable but are actually plastic.

Polylactic acid is a plastic commonly made from corn. It’s marketed as natural and biodegradable. Both of these are technically true but there is a lot of nuance to the situation that makes the products susceptible to greenwashing and increasing the impact of pollution, and negatively impacting recycling systems that actually recycle. PLA will only break down at a temperature greater than 60°C.

As consumers are becoming more aware of the environmental impact of their purchasing decisions, they are starting to ask for more from brands.

For brown “paper” packaging, look to see what symbols are printed. If it is uncoated paper, it can be recycled as paper (unless it is greasy, then it should be composted).

For paper products, if there is a glossy, plastic interior coating, that coating is plastic. The coating will likely either PE (petroleum-based polyethylene) or PLA (bioplastic from corn). If there is a recycling logo it is PE plastic. Almost all recycling systems can’t handle mixed paper/plastic products, which is why tetrapaks usually need to be thrown away. If it is PLA it will have a composting certification, you then need to determine if your composting system allows PLA.

For clear plastic containers, look for a recycling logo or a composting logo.

For plastic-like packaging, like cellophane, it is only compostable if your regional system supports bioplastics and it specifies that it is wood-based and compostable (and not a petroleum-based cellophane).

What products can be composted?

With your newfound knowledge you may start seeing greenwashing everywhere – even at small, well intentioned shops who are trying to do the right thing. Compostable packaging is much more expensive than plastic, so it’s really a question of who pays for it – does your small coffee shop lose margin, or do you pay more? Are you willing to pay 25 cents more for everything?

There are great products that can be composted anywhere, like:

Unbleached soft cardboard, which when grease-coated can be composted (greasy paper can’t be recycled)

Unbleached parchment paper can be used to make paper containers grease-resistant (such as preventing grease in transportation)

For bioplastics, you have to check if your municipal composting system allows for them. If they do, you can use products with the following logos or certifications. If your municipality doesn’t, you are aspirationally composting and creating higher composting costs and wastes. Toronto uses bioreactors for composting, as part of their composting process they shred all of the waste and then filter out all the plastic, which is then sent to a landfill.

Doesn’t composting create methane?

Methane is very complicated to discuss – it’s a potent greenhouse gas, 25x more potent at trapping heat than CO2. But it’s a very different gas – methane only lasts for 12 years in the atmosphere, and CO2 lasts from 500 to 1,000 years.

Methane is a natural product of decomposition and fermentation. You make methane in your digestive system. Cows make methane. Trees make methane. Landfills make methane. It is part of life and death.

There are many methods of dealing with methane, such as methane capture, which works in closed-composting systems (vessel composting and bioreactors). This can then be used as a renewable (but CO2 intensive) energy source. Check out this bioreactor being used to power an off-grid farm’s natural gas for cooking and water heating.

Methane is frequently brought up in the discussion around cattle and the dairy industry, but in that case there are ways to reduce methane production by adding seaweed to a cow’s diet. I’ll be discussing this more in next week’s topic, regenerative farming.

Nitrogen, which is a core part of agriculture as fertilizer, is 300x more potent than CO2 and lasts for 100 years in the atmosphere – more than a lifetime. Nitrogen fertilizers are typically made from fossil fuels, contributing vastly to nitrogen pollution. Composting (and regenerative farming, which is another form of composting) is a way to enrich and rebuild soil without dramatically altering Earth’s natural nitrogen cycle.

So while methane is problematic in the context of our CO2 and Nitrogen problems, eventually we can reach a circular, predictable amount of methane emissions on the planet. The same is true for nitrogen and the nitrogen cycle.

How can legislation help?

The City of Los Angeles, in 2023, finally introduced composting to their regional system. The only reason this was introduced was to comply with California’s new food waste law, passed in 2021. Without this legislation, all food waste would still be going into landfills where it will remain forever.

This can be effective at municipal, state/provincial, and federal levels. These are systemic problems that require Government mandates, regulations, and solutions to make the real change that needs to happen.

Food is political and you need to vote to make a difference.

What can I do at home?

Changing your habits at home to divert compostable waste from landfills is one of the best things you can do for the planet. Research your local composting rules and print out a list of what’s allowed and not allowed in your green bin. Google “my region green bin” and read the official website.

It doesn’t matter what the packaging says, it matters what you region system supports. If your system doesn’t support bioplastics, catch your waste in brown, unlined paper bags (like the kind kids used to take lunch to school in).

In the kitchen

In the kitchen, have a stainless steel composting bowl out as you are cooking. It’s a great habit that will make it easier for you to clean as you go, and it helps keep your counters and cutting boards cleaner.

I have this beautiful walnut compost box from Alabama Sawyer which uses stainless steel steam table pans and lids. You can buy stainless steel steam table pans at any kitchen supply store or online. These are far better than the plastic kitchen compost bins – they fit bin liners (if your system supports them), they can go in the dishwasher, and they are recyclable. You can have two, so one is always clean! You don’t have to worry about mold or smells with stainless steel.

If you live in a hot climate, you can keep stainless steel compost bins in the freezer, instead of on your counter, to prevent bugs and smells. If your system doesn’t support PLA bin liners, line them with wood shavings to help everything fall out.

If you have outdoor space and budget for your own composting system, they are great and give you plenty of rich soil (for free!) for your gardens.

Politics

If your region doesn’t have municipal composting, you can lobby your local politicians. Often political discussions are focused around state/province or Federal issues, but this is a local issue. Write to city and regional officials. Talk to your neighbours and get them to write. Be loud about it. Be willing to pay more taxes for it.

If your regional politicians aren’t supportive, lobby at the state/province or federal level for mandates. California passed a statewide mandate in 2021 and now even stubborn Los Angeles is composting.

If you live in a private residential area, like an apartment, condo corporation, or HOA, waste management is done by third-party services contracted by the corporation. Lobby the Board to add composting. If they say they can’t, that’s incorrect – they don’t want to. It adds costs. If you really want to make a change, join your Board. (I used to be on a condo Board, it’s not for the faint of heart).

If you are a restaurant or shop owner, you can also pay for composting disposal. Whether you want to prioritize your margin or the planet is your choice to make. You can also lobby the city/region and city council to make these changes to better support local businesses.

Can composting save us from plastics?

Scientists are working to solve the plastics problem. Even if we stop using plastic tomorrow, all the plastic we’ve created will still be on this earth. There are new bacteria being discovered, new enzymes being developed that can break down plastic into polymers existing bacteria can break down. This will happen in our lifetime, but technocratic solutions tend to come with their own new problems.

It’s better to not use plastic. It’s better to compost what you can.

And it’s even better to get your Government to implement the systemic solutions that will save our planet.

Next week: how chickens can save the world.

Marko